| Price List

|

|

|

|

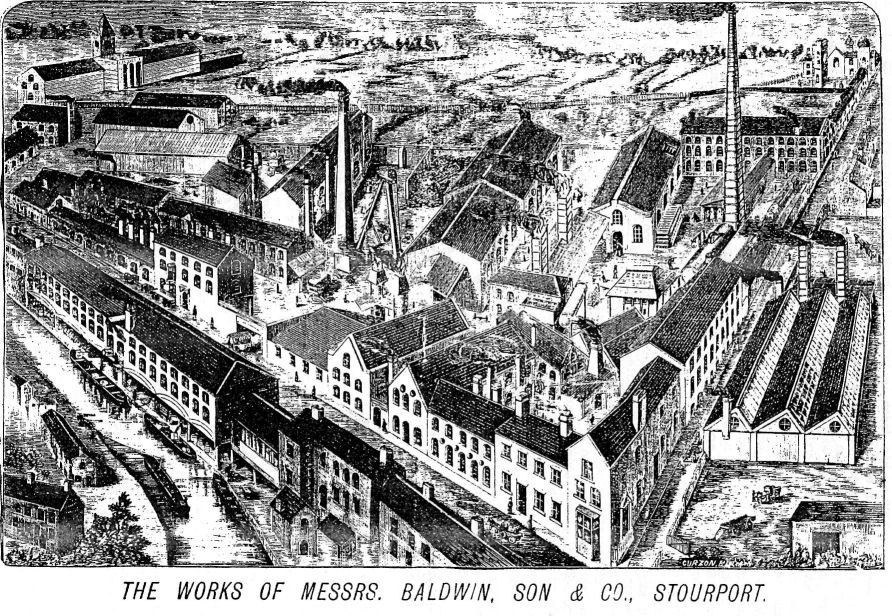

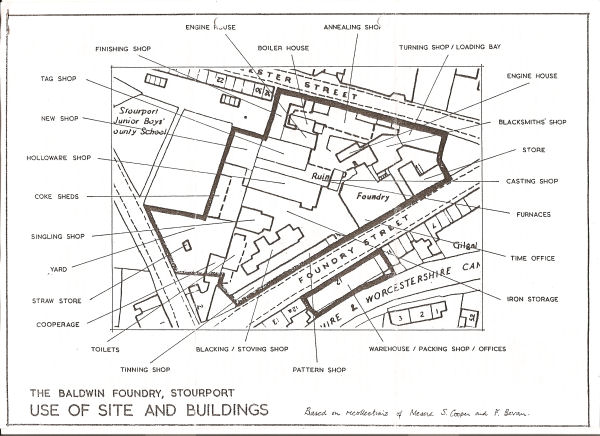

It is difficult to find out exactly when the Foundry was established. A sale notice of the leasehold of the Foundry dated 1822 mentions three separate leases for parts of the Foundry premises dating from September 1778, September 1779 and December 1781. So it would appear that the Foundry was established at some time in the 1770s. The Hawkswood family owned the Foundry premises but whether they themselves operated the Foundry is unclear. I L Wedley claimed that the Baldwin name first appeared in a Levy Book of 1789 but that the Foundry at this time appeared to be run by Joshua Parker & Co. The name of Thomas Baldwin (1751-1823) first appears in connection with the Foundry in 1813 when he and William Hill signed a twenty-one year lease to the Foundry with Thomas and Sarah Hawkswood. It is interesting that in that same year 'Mr Baldwin, Foundry' was quoted as one of the subscribers for a new Town Clock at Stourport. In 1823 Thomas Baldwin' s two sons, George and Enoch purchased the freehold of the Foundry from John Hawkswood for £2,300. It was under the influence of George and Enoch Baldwin and later, George's son, Alfred (1841-1908) that the firm grew to prosperity, acquiring an international reputation for the quality of its hinges. Buildings on the site rapidly expamed. James Webb of Worcester, undertaking a valuation of the premises in 1839, estimated that more than £6,000 had been spent since 1826. He commented:'The situation on the banks of the Stafford and Worcester Canal is admirable and. its proximity to the Severn gives the proprietors great facilities for exportation and enables then to compete with any similar manufactory in the transit of goods to Bristol or Liverpool.' The annual turnover of Baldwin Son & Co in 1863 was £27,076. 12s. 4d. In addition to the Foundry at Stourport, a forge at Wilden was built in 1849 for the production of wrought-iron, while the family's business interests included worsted spinning mills at Stourport, a carpet factory at Bridgnorth and. a tin-plate works at Wolverhampton. When Alfred Baldwin died in 1908 he was worth a quarter of a million pounds. About 1860 a division of interest in the iron works had taken place. Enoch Baldwin continued in charge of the Stourport Foundry under the name of Baldwin, Son & Co., while Alfred' s brothers and half-brothers ran the forge at Wilden under the name of E P and W Baldwin, by which style the firm was known until it amalgamated with others and 'went public' as Baldwins Ltd in 1902. In 1886 Baldwin’s Foundry became part of Archibald Kenrick & Co of West Bromwich, a firm which produces similar holloware products. The Baldwin name was retained and members of the Baldwin family were on the Board of the amalgamated Company. The Stourport Foundry continued to specialise in hinges whereas the speciality of the West Bromwich plant was the famous Shepherd castors. All marketing and sales were centrally administered by Kenricks. During the course of the twentieth century the demand for hollow-ware declined quite markedly. Documents in the Kenrick Company archives quote the output by value for hollow-ware as being 430,427 units in 1923 whereas by 1955 the figure had fallen to 36,168. This was due to the introduction of new materials such as aluminium and stainless steel and also changes in fashion. Suggestions were made that the Company should try to diversify by producing baths, cisterns and other more popular domestic products. In 1937 Kenricks appointed Peak, Marwick, Mitchell & Company to draw up a report on the state of the Company and made recommendations. The Report presented to the Board ;va8 critical about the administration of the Kenrick Company and the reliance on members of the family rather than trained administrators. They suggested the appointment of 'a vigorous, full-time Chief Executive Officer' to oversee a programme of modernisation. Kenricks themselves accepted the comment that much of their foundry equipment was out-of-date but seemed reluctant to bring in outsiders to run the Company. In 1950 A W Baldwin was still urging them to implement the recommendations of the Report. They did finally appoint a professionally qualified Chief Executive in 1950. However, time was running out for Stourport Foundry. In January 1956 most of the employees were given one week's notice and later that year, on December 10th 1956, Worcestershire County Council issued a Discontinuance Order, quoting the Town and Country Planning Acts of 1947 and 1950. The 1947 Local Development Plan had designated the surrounding area as a residential zone and this meant that the use of the premises as a foundry would have to cease, as only light industry could be carried out in that area. Many older inhabitants of Stourport no doubt remember the amount of smoke emitted from the Foundry chimneys! The derelict Foundry buildings were finally demolished in 1967 and the new County Buildings built in 1972. All that remains today is the building which housed the warehouse and offices which is now occupied by an aquarium business and snooker club. | |

|

|

Mr FRED BEVAN TALKING ABOUT THE ANGLO AND THE FOUNDRY 1917:(as dictated to Stourport Civic Society 1992) When I started work, I went home from school just after my thirteenth birthday and Dad

came home and he says 'you aren't going back to school; I've got a job for you.' So I went

to school in the morning and work in the afternoon.

56 hours was the standard week then and I had 5 shillings a week -25 pence a week and I thought

I kept the home, you know. That was at the Anglo Enamelware Limited, in the Time Office;

There were two sections to the Anglo, the one in Mitton Street, the other in Baldwin Road"

There was a whistle on top of the boiler; a cord or a wire used to go all the way from the

time office to the top of the boiler, and if you pulled it it opened a valve and the whistle

blew. This used to have to be blown at five to six in the morning, and at five

to nine when it was breakfast time and at five to two when they came back from their dinner,

then you worked to half past five. At that time the war was on, and for years and years they made water bottles for the army, literally hundreds and hundreds of thousands of them. They brought what we call tinkers down from the Black Country and the bottles were made by hand; they were covered in felt, had a cord on and a cork in the top, and they were enamelled. They started with just a piece of metal. Well it got to the point where they couldn't keep up with it by hand, and from America they brought a machine which made the tins: the bottle just went round a time or two and the bottom was on, whereas before it was actually knocked on, all the way round. Then about that time spot welding came in and they used to rivet the neck on. The war brought that about. But ordinarily, in everyday life, they used to make practically everything in enamel; and why the enamelware that they made was so good was that it didn't rust. They put a coat of what they used to call 'grey' underneath (so that it did not rust if chipped). They sent to India millions of rice bowls, and they found it was cheaper to build a factory in India and make the rice bowls out there. In the office where I worked, all along the mantleshelf was a row of enamel plates, and on them were all the different ships; They would have an order for so many thousand plates for HMS Ebenezer or whatever it was. There was always a very very big show in Hamburg in Germany and you know, there was no one to touch them at all. They've done enamelware that you'd think was porcelain. That was a real job that was; they could not afford to do that. I worked there about two years, then there came a vacancy tor a young lad up at the Foundry (the same people that were Kendricks at West Bromwich owned both the Anglo and the Foundry. The 'Baldwin' name never changed). I used to have to make the railway consignment notes out. At that time there were two railways - the London Midland & Scottish which had their headquarters in Mart Lane; that's where the boats ,were loaded. But everything for the Great Western, by goods, was col¬lected by Thomas Bantocks; they had the horses and the drays. I used to have to ring the station every morning and find out what stations were open that we could send to; this was the immediate aftermath of the war. They made more hinges, door hinges, at the foundry than all the rest of the firms in the world put together. From the station they used to bring pig iron bars, pick them up and drop them on a piece on the floor - there was a knack in 'dropping them on' - it would break the bars into pieces which was then put into the cupola and melted. If you got a Baldwin hinge, they never wear out, nobody could ever understand how the pin got in the middle. They made half the hinge, then they put the pin down inside and they covered the pin, with the finest camel hair brushes you could get , with whale oil, dipped them in sand so it stopped the iron; On the back of the hinge, so that it wouldn't stick, they used to use pitch, just dab it on. Then they put that half into a box and poured the box and made the other half - so the pin was in the middle. So really the whole thing was made by hand. And they made cores; that's how they put a hollow spout on a kettle. Different Parts of the country used different cast-iron saucepans. And they used to make maselines to do jam in and those were enamelled inside. They made quite a lot of , kitchens', with a brass tap in the front; you put it on the side of the hob (for hot water). When the war was on they made hand grenades; nearly every house in Stourport had got a foundry hand grenade; they used to blacklead them and polish them and put them on the side of the grate! If you go up and look in the old churchyard, you will see cast-iron grave stones that were made in the foundry. And Mr Isaac Wedley's brother, Mr Bill Wedley, he used to do all the odd work and he made the church door hinges - they would be 6-8 feet long, all scroll,you know. Another thing they used to make, cast iron boot scrapers: one of those was always outside the door. They invented, and they are used to this day, skew-butts, lifting hinges. Incidentally, the foundry was the first place to be lit by gas. They used tons and tons of sand, and that came from Masons sandhole up by Oldington; a man used to pull it down the canal - he'd got a padded rope round him and off we go, he'd bring it down to the foundry. And that was the reason that the tunnel is under Foundry street. They filled the barrows and wheeled them up and under and into the foundry. There was also another went under Worcester Street into the part where they did the enamelling. Stourport was a marvellously industrial place: we had the vinegar Works, the Gas Works where I used to go with Dad to fetch the tar to caulk the seams of the floating bandstand, and there was the Textile over the Stour Bridge. The Tannery was a real going concern; there was the Anglo and the Foundry, and Baldwins at Wilden. And Worths. As I say, I left school at 13. Never once did it ever enter your head or crop up that you hadn't got a job to go to; if you were out of work, you wanted to to be out of work. That's gone. |

|

|

|